In a more sensitive age the Victorian novel shocked its readers with vague allusions to sexual encounters, frigid conversational faux pas, marital gaffes and tales of social rejects daring to reach beyond the mandate of their class. A misplaced glance or an uppity remark were enough to see a stiff eyebrow raised in disapproval. Since then our taboos and limits have shifted. The invention of film brought us closer to the knuckle, its immediacy gave it mass appeal, bringing the human body, violence and sex to the masses.

Prose has always possessed an ability to portray something whilst simultaneously keeping the reader distant, and this has allowed it to breach issues so troubled that they remain taboo even today. Nabokov’s examination of pedophile Humbert Humbert in Lolita is one such example. The novel is carefully structured to veil the difficulty of the subject matter, employing several techniques that distance the reader from the reality of the subject. The main text is bookended, so to speak, by police accounts framing the narrative as a cautionary tale, a record of the sick exploits of a desperately ill man. Humbert’s narration is intelligent, humorous, technicolour prose, reveling in the flamboyant ego of its protagonist; its unreliability all the while cautiously masking the dark subject matter at its heart. Lolita was no stranger to controversy, and despite these distancing measures there was no denying the corrupt eroticism at the novel’s heart, the book found itself banned for the first years of its life. In time, however, it has not only been allowed to enter the public consciousness, but it has thrived, and is regarded today as a literary classic.

Cinema, meanwhile, has failed to convert the story of Lolita well, finding itself unable to adapt these literary techniques into its own armoury of tricks and tropes. Kubrick’s attempt places Humbert’s humour at the beating heart of the film and the resulting farce undermines the pathos of the tale. Lyne’s adaptation took the cautionary approach to arguably poorer effect. Both struggled with their inability to convey the nature of Humbert’s dangerous fixation visually, they lacked a language that society would accept. In a new age we have another medium to consider, and this one has the potential to bring us closer to the subject than ever before. In games, the player has the power to experience content as closely as they want, and the question is: does interactivity make things too close for comfort?

It seems clear that games have the power to move beyond the simple voyeurism of cinema. As well portrayed and detailed a world as it was, I could never actually walk the streets of Scorsese’s construction of New York in Taxi Driver. Until the game I could never tread the murky, drowned streets of Bladerunner. The planned Bioshock film will no doubt copy the astounding decimated 40’s underwater noir aesthetic, but I suspect I will never know it the same way I came to by exploring Rapture myself. The ability to roleplay, and to properly occupy a world is powerful and unique to the medium. Greater interactivity coupled with ever evolving technology, improved graphics, more expansive sound and ever more detailed game worlds means a greater sense of immersion for the player. But will it ever be considered acceptable to roleplay Lolita’s corrupt protaganist?

This question lays bare many of the assumptions we carry about videogames and their purpose. Roleplay Humbert Humbert? Why would I want to? People read the book and watch films in order to be challenged, to see what the fuss is all about, and to investigate a piece of work that touches upon a dark and rarely explored phenomenon. This is an experience that nobody would expect to receive from a videogame because, well, they’re just mindless escapism aren’t they? Games aren’t meant to be difficult, that’s not what they’re for.

From the very beginning people would visit cinemas and pay to see a news report, since then millions have sat through Schindler’s List, and they didn’t do it for a bit of mindless escapism. They paid money to watch three hours of despair, to see the worst human nature has to offer come bleeding through the projectors, to walk out shocked and dejected, and to see the world in a slightly new light. The videogame genesis took the form of Tennis For Two, which was just a very clever toy, a side project to amuse the scientists while they went about the more serious business of building big machines. Games have continued in a similar vein ever since.

Behind the pretence that videogames are just toys there is a more substantial fear which motivates much of the hysteria surrounding videogame content, the fear that interacting with a virtual world leaves one more susceptible to any disturbing influences it might carry. The mainstream view of videogame violence, punctuated by almost weekly bashings in the conservative press, constantly reinforces this notion, often with emotive stories linking games to real life murders, with claims that these real acts were copied from, or somehow directly influenced by in-game actions. The assumption that someone involved in an interactive experience loses sense of what is real is the most ludicrous assertion to come out of the arguments and hyperbole surrounding videogame content. Graphically games are advanced, but not photo realistic, and the suite of actions available to players is so contrived that, without suffering from a mental illness (or having this happen), it is impossible to confuse videogame actions with real ones.

This accusation is often ignorantly thrown out as a knee jerk reaction to offensive content, and often masks the real concerns that people have about videogames. The most disturbing element seems to lie more in the symbolism of committing a virtual act of violence, with the assumption that the virtual act is a form of wish fulfillment. The fact that game violence is a strong selling point shows that there is a profitable desire to dish out spectacular death among the population, violent games sell directly to the primordial parts of us that revel in destruction, the part of us that society tries to keep contained as much as possible.

This becomes especially problematic in games offering purely linear experiences that revel in violence and little else. In this environment the player walks the path carefully laid out for them by the developers, an obstacle course of various horrific acts, a bloody fairground ride that challenges the player to match its preordained levels of violence and horror. Manhunt, and its sequel, are naked examples of the disturbing appeal that some games possess, but the real controversy stems from its honesty, its refusal to disguise its core selling point. Manhunt simply lacks the tokenistic pavlovian punishment/reward system commonly used as a veil to lessen the impact of in game brutality, and to sustain an illusion that the game is reinforcing society’s moral code.

It’s this moral code that prevents games from dishing out points or providing immediate gratification for the unprovoked killing of innocents – a phenomenon that caused mainstream controversy when observed some years ago in games such as Carmageddon and the first Grand Theft Auto, and which can only be found today very occasionally in the likes of God of War, which, in one or two sequences, allows the protagonist to dismember fleeing civilians for a quick health boost. The fact that games are seen to need to reinforce ‘good behaviour’ are a hangover of the perception of games as children’s toys, whose purpose should be to entertain, perhaps to educate, but never to glamourise or encourage antisocial habits. Today this developer imposed morality acts as a form of distancing, the gaming equivalent of Lolita’s police accounts, providing window dressing in the form shallow B-movie storylines, pitting the player against suspiciously humanoid alien foes who, when cut, still bleed like us, or, most depressingly, casting Nazis as the villains, whose death and dismemberment is considered innately acceptable.

The side-effects of this prove damaging. Games often still treat us like children, protecting our fragile minds from the grey ambiguity of real human choice by providing us with colourful cardboard cut-out visions of good and evil. In Fable we’re given two-tone quests and the ability to evolve into a saint or satan himself, in Bioshock the much hyped moral decisions surrounding the Little Sisters were neutered to the point that it had little impact on the storyline, the consequences of the player’s actions instead took the form of two possible endings which squatted so far apart on the good/evil scale that it was almost laughable.

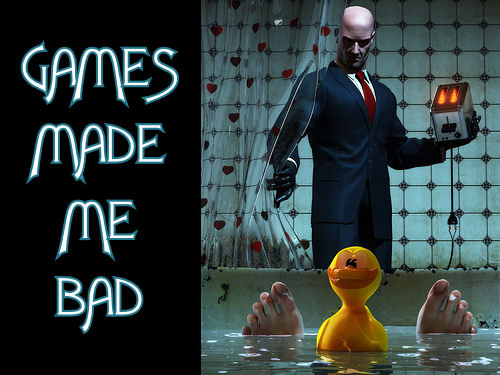

This problem has been circumvented in recent years with the prevelance of open world games which, thanks to improving technology, are now larger and more involving than ever before. Good open world or sandbox games empower the player by providing them with more tools, more ways to interact with the virtual world. By granting a degree of creative freedom these games give the player a say in the content of the game, allowing him to mediate the levels of violence within it to his own standards. Take Hitman: Blood Money for example. Following an FBI bodyguard into a dark corridor and plunging a kitchen knife into his neck to steal his clothing is an option, but it’s just as easy to slip some sedative into his tea. After a night of drinking in GTAIV you don’t have to get into your car and drive, you can hail a cab. In a sandbox environment the player is required to take more responsibility for his actions. Just because the game gives you the tools to commit heinous acts doesn’t mean you have to utilise them. The responsibility for violence in games shifts from the developers to the player.

This movement of responsibility has the potential to take censorship out of the hands of the conflicted ratings authorities and into the hand of the individual adult, where spurious media assertions can only have so much impact on the well-informed mind. More importantly, offering the player control of their play leads to more mature game experiences, free of the cartoon black and white good an evil concepts of something like Fable, more mired in the ambiguity of human experience.

This is perhaps most spectacularly evidenced by the tumultuous happenings in the vast space MMO Eve Online. Eve Online’s omnipotent overseers are morally indifferent entities, ruling as the philosopher’s god, sustaining the technical integrity of their world with little desire to mediate what happens within it. Eve’s ‘shit-happens’ approach has birthed some spectacular stories, grown entirely out of the friction between its vast and complex groupings of human participants. These tragedies and space operas are all the better for the fact that they have been allowed to evolve unchecked from the syrupy nastiness of human nature. Betrayal, theft, assassination, murder – the stuff of great drama is on show for anyone to be a part of.

There is a fear of games that can be applied to any artistic medium, a fear that they will act as a crucible for our darker desires, allowing for a space where graphic violence is sanctioned and can occur without consequence, with unprovoked abandon, a place for our alluring dark sides to fester. Upon asking friends and family of their experiences with violent videogames I discovered that one member had a particular habit. She had found a convenient rooftop in San Andreas that the police could not reach. Tooling herself up with weapons cheats she would proceed to snipe passers-by (“only in the head”), until her wanted level peaked. “Then the helicopters come, but I just shoot them with the rocket launcher”. When asked why she would do such heinous and terrible things she replied “I was bored”, when quizzed on the appeal of mass destruction the reply was concise: “because it’s really funny!”

It goes without saying of course that this particular person has never been arrested, and has never displayed any violent or criminal behaviour in real life, but her gaming habits did find her indulging a darker side. When finally asked why she didn’t feel bad about her carefully planned killing sprees she dropped a rather potent observation, a pearly brick of pure uncut wisdom which, for the sake of any concerned and overzealous mainstream journo I would have printed in big friendly letters on the front of every retail edition of Manhunt and all its ilk.

“It’s not real.”

Ultimately, developers creating adult games, as forms of art or entertainment, shouldn’t be required to relentlessly reinforce society’s moral line, but should instead be allowed to produce stories and situations that challenge us. Games, like other more accepted media formats, can, will and already have visited those dark, violent, id-ridden spaces that entertain us, and they shall continue to do so whether the ratings organisations or the conservative press like it or not. What will remain true is that much of the thrill of an adult virtual environment lies in its subversiveness, its power to allow you to roleplay actions that you could never perform in real life. In a young medium which has yet to find its limits, and that has yet to learn subtlety or restraint, with evolving gaming technology and open worlds, the question is increasingly being asked of the player, in a bloody virtual future – how far will you go?

Ludo out.